22 days. 16 states. 7 national parks. A grief retreat. A stolen license plate and rear vision camera. Weather ranging from 30 to 96 degrees. The road trip of a lifetime in a Porsche Boxster, using back roads wherever possible. We are talking close quarters for a long time.

My husband always wanted to take a driving trip out west and he really wanted to drive the Beartooth Highway in Montana. This was his dream trip. Bob is my soul mate and the best husband imaginable, so how could I refuse?

We’ve talked about this trip for years but never could seem to make it happen. Then, in a short period of time, we lost Bob’s mom and my dad. A grief retreat was in order and this was just the trick to get us started.

I was intrigued by the Spark of Life retreats because they were free. As a nonprofit executive, I’m always interested in how other nonprofits do what they do. Aside from that, I needed to deal with my grief. More on that in another post, later.

Someone said once that the planning of a trip is as much fun as the trip itself. Bob poured himself into the planning. My physical therapist warned Bob to stop every hour or so, in order for me to walk around. I didn’t want to go more than about 300 miles each day so that we could have time to check out the sights. I didn’t want to just drive through a state without stopping for an adventure.

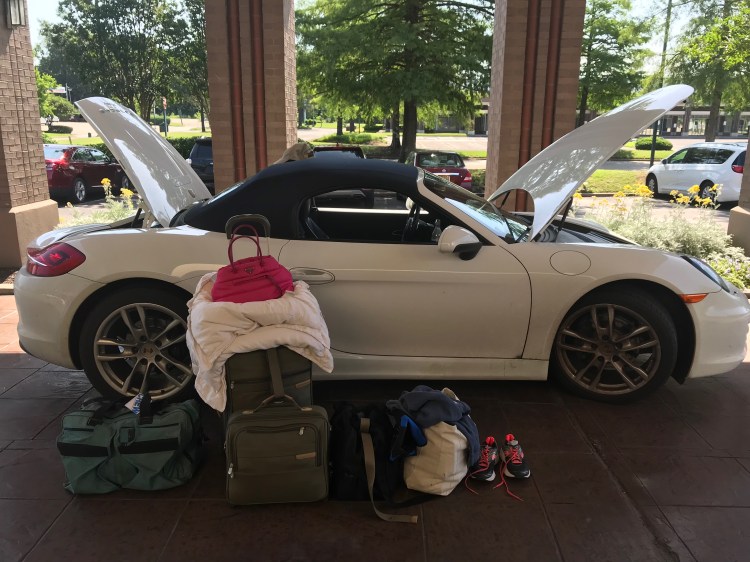

Packing was another story and my packing checklist will be available soon on my website under products and services. The Boxster has a front trunk and a rear trunk but that isn’t a lot of space. Somehow I had to get it down to two pairs of shoes and clothes for both hot and cold weather. Efficiency was key. One of my dearest friends and traveling role model, Sheila, said we should plan laundry every 4th or 5th day. My favorite cousin said stay at a hotel for two nights and let them do our laundry. Either way, this solved the problem of clothes for three weeks in a Porsche.

It was Day 2 when our license plate and rear vision camera was stolen in Missouri. We filed a police report and wrote down the officer’s name, badge number, phone number, and report number. You can’t be too careful.

We went up the arch in St. Louis and we tugged on Superman’s cape in Metropolis, IL. We saw the faces on Mount Rushmore and hiked around Devil’s Tower. We spent two days in Yellowstone and drove to the top of Rocky Mountain National Park. We cried during the film at Big Hole National Park. We stood beside giant dinosaur bones at Dinosaur National Park. We learned we could apply to be volunteer park rangers. We ate at local restaurants and learned the stories of everyone we met.

By Day 20 we were ready to be home. We stepped up our pace. It was time to sleep in our own bed. I couldn’t stand the thought of dragging my luggage into a hotel one more time.

It as a bittersweet moment when we drove into our garage. We love our home and we were happy to be home, but the three weeks on the road had been heavenly.

We’re already planning for 2019.